|

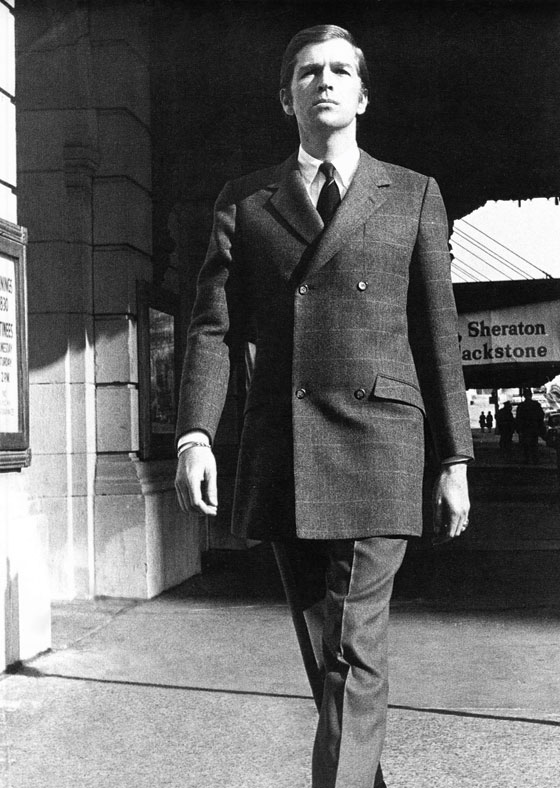

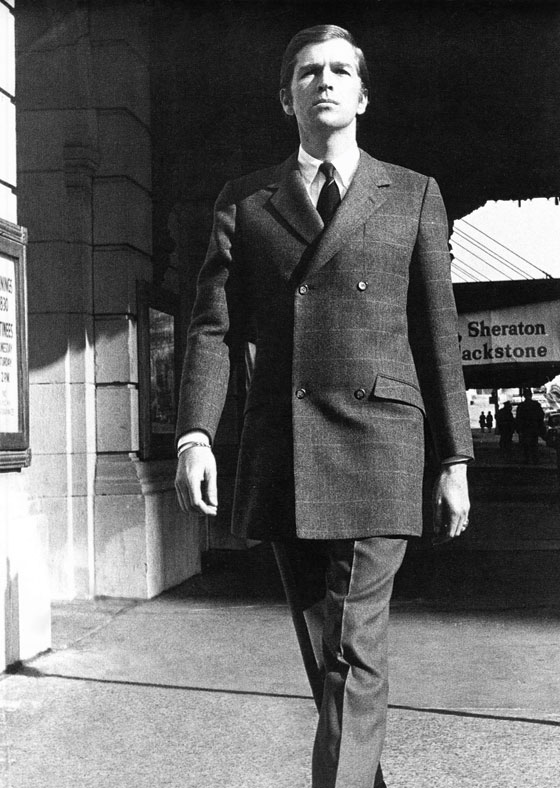

Clayton Coots in front of the Blackstone Theatre in 1966.

|

In a new century dominated by terrorism and recession, few would deny two big bright spots: the election of an African-American president and the expansion of gay civil rights. The first arrived nearly 150 years after the Civil War. The second happened with the speed of a fever dream. The modern gay-rights movement only got going in 1969, after the

Stonewall riots. Now a dozen states have legalized same-sex marriage, a concept unknown in political discourse a mere quarter-century ago. More astounding is the likelihood that a conservative-leaning Supreme Court will expand those marital rights, however incompletely, next month—it took more than a century after the Emancipation Proclamation to end all bans on interracial marriage.

As we just learned, a man can still be

murdered for being gay a few blocks away from the Stonewall Inn. But the rapidity of change has been stunning. The world only spins forward, as Tony Kushner wrote. And yet as we celebrate the forward velocity of gay rights, I think we must glance backward as well. History is being lost in this shuffle—that of those gay men and women who experienced little or none of today’s freedoms. Whatever the other distinctions between the struggles of black Americans and gay Americans for equality under the law—starting with the overarching horror of slavery—one difference is intrinsic. Black people couldn’t (for the most part) hide their identity in an America that treated them cruelly. Gay people could hide and, out of self-protection, often did. That’s why their stories were cloaked in silence and are at risk of being forgotten.

This history is not ancient. My own concern about its preservation comes not from some abstract sense of social justice but from my personal experience. I grew up in the Washington, D.C., of the sixties, where the impact of racism was visible everywhere, front and center in my political education. But gays—what gays? No one I knew ever saw them or mentioned them. Not until the eighties—when, like many Americans of that time, I was finally forced by the rampaging AIDS crisis to think seriously about gay people—did I fully recognize that a gay man had been my surrogate parent in high school, when I needed one most. Not that I ever thought to thank him for it.

For younger Americans, straight and gay, the old amnesia gene, the most durable in our national DNA, has already kicked in. Larry Kramer was driven to

hand out flyers at the 2011 revival of

The Normal Heart, his 1986 play about the AIDS epidemic, to remind theatergoers that everything onstage actually happened. Similar handbills may soon be required for

The Laramie Project, the play about the 1998 murder of the gay college student Matthew Shepard. A new Broadway drama,

The Nance, excavates an even older chapter in this chronicle: Nathan Lane

plays a gay burlesque comic of 1937 who is hounded and imprisoned by Fiorello La Guardia’s vice cops. Douglas Carter Beane, its 53-year-old gay author, is flabbergasted by how many young gay theatergoers have no idea “it was ever that way.”

Clayton Coots, the gay man who changed my life, fell somewhere between

The Nance and

The Normal Heart on this time line. He was one of countless gay people who were hiding back then, sometimes in plain sight, from their friends, neighbors, relatives, students, and colleagues. In historical terms, back then was only yesterday. Yet much as we might want to reclaim these invisible men and women from the shadows, they continue to slip away. It’s one thing to retrieve the story of a gay American from the pre-AIDS era who was famous or notorious. It’s quite another to track down a closeted gay American of no renown who lived shortly before the gay-rights revolution took hold. I have spent more than twenty years off and on trying to piece together Clayton’s life. Even in death he is still in hiding.

When I met Clayton, he was a company manager for touring Broadway shows and I was a stagestruck high-school junior just turning 17. We crossed paths at the National Theatre, a busy Broadway touring house in downtown Washington in the pre–Kennedy Center era. I had landed a part-time job there as a ticket taker. Most of the visiting show people I met were characters out of

Broadway Danny Rose. But not Clayton, who hit town as the manager of the tour of Neil Simon’s first big hit,

Barefoot in the Park. Then about 30, he was younger than his peers, as handsome as a model, and came to work each day as if he were attending a glamorous opening night in Times Square rather than cooling his heels in the provinces. He always wore a Pierre Cardin tux to the theater, with accessories to match—a Patek Philippe watch, glittering cuff links, and a long black-and-gold cigarette holder that matched his Dunhill lighter. (He would soon instruct me in these brands.) He took an interest in me from the start, chatting me up about school, my family, and the only subject I really cared about, Broadway. It was the first time any adult in the theater had taken me seriously, and I was flattered and dazzled and entertained. He was a perpetual wisecrack machine, wry but not bitchy—“the closest I ever got to Noël Coward,” as one theatrical colleague of that time would later recall.

Ancient Gay History

ShareThis

Our running conversation lasted for the first three weeks of

Barefoot’s summer

run in Washington, after which Clayton was heading to Chicago for an extended stay managing the road company of a newer Neil Simon hit,

The Odd Couple. As it happened, I, too, was heading to Chicago for the summer, to attend a course for high-school journalists at Northwestern. Clayton told me to look him up if I wanted to bring any friends from Evanston to Chicago to see his show.

Some weeks later, just as my course was ending, I left him a message with the switchboard at the Blackstone Theatre in the Loop. I had decided to spend an extra weekend in Chicago to be with a girl I’d met at Northwestern. I hoped to take her to see Dan Dailey and Richard Benjamin in

The Odd Couple. But by the time Clayton called me back, the girl’s mother had changed her mind about letting me stay with them. He immediately suggested that I bunk at his apartment instead, if it was okay with my folks.

That turned out to be the day I first heard the word

homosexual—in my stepfather’s ensuing question on the phone: “Do you know if he’s homosexual?” I gathered this was not a compliment and said I was certain that Clayton was innocent of the charge. But my stepfather wanted to verify: He would call the manager of the National Theatre and ask. The verdict arrived a few hours later. My boss had vouched for Clayton, and so I could stay with him for the weekend. It never occurred to either of my parents (or to me) that the National’s manager, whose ticket-taking staff consisted entirely of young, single men, was also gay—in hindsight a larger-than-life queen worthy of

The Nance. Such was the closeted world, even in the theater, as seen by those on the outside looking in, circa 1966.

What started that weekend in Chicago was the most intimate relationship I’d had with any nonparental adult. It was, in retrospect, a chaste and mostly epistolary love affair. In those days when people still wrote letters, Clayton and I often exchanged two or three a week, his densely typed on regal-blue stationery engraved with his name in large capital letters, or, even more romantically to my mind, on

Odd Couple stationery festooned with the show’s logo. Since my stepfather was an airline lawyer, I could wrangle occasional free plane tickets back to Chicago. I’d travel there to visit my girlfriend on odd weekends, each time staying at Clayton’s apartment a few blocks north of hers on the Near North Side. Clayton would take the two of us out after his business was done at the Blackstone, and he schooled us in fine dining, in drinking brandy, and in overall bonhomie at watering holes like Punchinello’s on Rush Street, where the casts of every touring show in town gathered after their final curtains. It was preposterously glamorous. Clayton knew everyone in Chicago and everything about the Hollywood movies of the thirties and forties he watched nightly on the

Late Show. He was an accomplished classical and saloon pianist; he spoke German and French, which he had picked up on a checkered path through European boarding schools before forsaking college to enter his father’s calling of show business. His dad was the songwriter J. Fred Coots, the author of Tin Pan Alley standards of the thirties like

“You Go to My Head” and

“Santa Claus Is Coming to Town.” Clayton made a point of saying that he got no money from home. Making ends meet was a constant worry, particularly given his serious clotheshorse proclivities, his generosity about picking up checks, and his insistence on showering cast, crew, and friends alike with extravagant presents on birthdays and holidays.

In person and in his letters, Clayton talked about various girlfriends of his own, one of them a touring musical-comedy belter I’d seen in

How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying at the National. But these women never materialized in the flesh. Not that I minded. What mattered to my narcissistic teenage self was that Clayton was interested in me. I was an unhappy child of divorce. My mother was in her second stormy marriage. I was always one step away from running away from home. In his letters, written with the salutation “Dear Pal Frank,” out of

John O’Hara’s Pal Joey, Clayton would try to steer me back on track with what he called “Big Brother Lectures” about minding my studies and my parents and not feeling sorry for myself. “Life is beginning, not ending!” he wrote in one pep talk. “You don’t help yourself by allowing the loneliness to take control and affect your life or your studies,” said another. When I fought with my mother, he defended her: “She may have problems you know nothing about.” He defended my girlfriend too: “Many times in the future Frank you are going to have to take loved ones only on faith and you may as well start learning now.” Then he would go back to telling me backstage stories about his cast, or reconstructing (dialogue included) a scene from the Mae West movie he’d seen on television the night before, or detailing his track-by-track reaction to the newly released

original cast album of Cabaret.

Ancient Gay History

ShareThis

By high-school graduation, Clayton had left The Odd Couple and Chicago. Now back at his nominal home in New York, he invited me for an overnight visit on my way to meet up with a school friend for the weekend. After a dinner at his favorite Italian joint, by the 59th Street Bridge, we went back to his apartment. At bedtime, Clayton made what even I could identify as a pass. I deflected it easily enough, and neither he nor I ever mentioned it again. It upset me, but not because I feared I was in any danger. What bothered me more was the realization that Clayton did have another life that he had never so much as alluded to in all our correspondence and conversations. My feelings were hurt more than anything else. I had told him all my humble secrets, but he had not reciprocated.

We stayed in touch as if nothing had happened, but less and less so. I was now at long last about to escape Washington for college, and it was perhaps inevitable that we’d drift apart. I had outgrown my combination Auntie Mame and Peter Pan. The last letters I received from Clayton were brief and uncharacteristically angry. He was furious at Marlene Dietrich, whose one-woman show he was managing on Broadway during my freshman year. She is “truly horrible,” he wrote, and treated him “as a dog.”

A decade or so passed. When, in 1980, a notice appeared in the Times that I had been appointed the paper’s drama critic, he wrote me a sweet note, saying with typical cheek that he knew I’d amount to something. I was overjoyed that he was back in touch at this of all moments. He’d been present at my baptism in the theater. I wrote back at once proposing that we get together and catch up. I never heard from him again.

By the early nineties, I had married for a second time, and as a surprise for my birthday, my wife, Alex, set out to find this Clayton I had talked about with such affection and who had been a solace to me at a low time in my life. Alex had once worked as a Broadway house manager, so she turned to her old union, which would have been his, to see what might be in the files. The answer was more of a surprise than she had bargained for: Clayton was dead. He had died almost a decade earlier, in 1984, when he was in his late forties. The loss felt like a body blow. I went to the Times morgue to find his obituary. There was none.

By then I was starting to think about writing a memoir about my youthful obsession with the theater and how it rescued my childhood. I knew Clayton would be a significant figure. But what did I really know about him? It would be impossible to write the book if I couldn’t locate his old correspondence. I anxiously retrieved the boxes of youthful detritus my mother had packed off into storage before her death, hoping that she hadn’t thrown out his letters along with my baseball cards. When I found the stash, I picked one at random and read it aloud to Alex. She at once recognized the voice, witty and sardonic and yet kind, that I had described to her.

But rereading the letters nearly three decades after they’d been written, I noticed much that had passed me by in high school. Though the invocations of romances with women were as plentiful as I remembered, they coexisted with a steady barrage of camp references and jokes that had flown right above my head. In one letter, he had sent a parody “review” he’d written of a fictional cabaret act starring Pat, his most persistent girlfriend. He’d named her backup group the Gayboys. “Gay” was not then in common usage as a synonym for homosexual. (“Fag” was, and Clayton used it once, repeating someone else’s wisecrack.) But while it’s conceivable Clayton’s use of “gay” was old-school, I now had to wonder. “The stunning outfits of the Gayboys,” he wrote, consisted of “skintight lavender pants, fuchsia boots and lime green tops.” Here was a code that I and much of America could crack by the late nineties but that was still impenetrable to the uninitiated in 1966.

What also struck me for the first time all these years later was just how unhappy Clayton was. Even as he constantly bucked me up, he confessed to blues of his own. “Oh how bad can Saturday nights be when you are alone on the road,” he wrote in one typical soliloquy during the dog days of August in Chicago. “Happily, I am well adjusted to life enough to keep cheerful and ‘up’ but there are times I’m not and I get terribly lonely as I am today. The theatre is dark, it’s cold and empty and I come here for there is no where else to go. You know what I mean. That hotel is great if there’s someone around, but that room can be depressing alone. What a strange business—so many people every day, so much to do, and so many lonely moments. Please don’t get mad because I’m writing of trouble to you, but these are things you don’t tell just anyone. Also, I’m sort of a legend around here and I’m always Happy and with it and this is a side you don’t show to just anyone. When you are a manager, your troubles come last and it’s the company that needs you and you owe them that. Anyway, these moments don’t last and there is no truth to the rumor that I intend to leap from the balcony some night.”

Ancient Gay History

He made a point of saying he didn’t confide in anyone else: “Frank, it’s funny, I tell you things that I’ve told no one, but maybe you understand.” I didn’t quite understand—he was a great man of the theater, how could there be any trouble?—but his feeling of being “alone and unnecessary and unloved” resonated in my teenage heart. I longed to emulate him, and sit at the piano and play Chopin nocturnes before I went to sleep, as he did, “to try to forget where, who, and what I am.”

Rereading Clayton’s letters, I realized he was the only adult I knew who freely admitted to feelings like this and would indulge me in conversation about them. And unlike anyone else, he was available whenever I needed him. “If you feel low on anything,” he wrote, “call me collect cause I’ll cheat the show out of the cost.” The source of his loneliness was unknown to me, though. It would be a cliché to say Clayton’s melancholy had to do with his sexuality, and it’s entirely possible it did not. But what was clear three decades later was that he was rootless, that he kept his deepest feelings under wraps, and that he was running away from something, most likely himself. Not for nothing did he keep moving from town to town on the road like Harold Hill, the irresistible hero of one of my favorite shows from childhood,

The Music Man. It was also obvious that I had had little to offer Clayton in return for all the empathy he had bestowed upon me. Much as he tried to teach me how to be a man—“Stand on your own two feet and don’t blame someone else; it does you no credit”—I was a long way from becoming one.

Once I started in on my memoir in earnest, it was not easy to find anyone who knew him more than in passing. The only family member he ever spoke of fondly—his mother, whom I had met with him briefly in New York—had just died, in 1997. I placed an ad in the managers’ union newsletter seeking anyone in the theater who had memories of Clayton. There were only a few responses, all from people who’d known him in the early seventies, after I had. I learned he had been a road manager for

Hair, surely the ultimate indignity for a man whose default wardrobe was black tie and whose one minor dispute with me was to question my opposition to the Vietnam War. One acquaintance of Clayton’s had attended his small funeral at a church on the Upper East Side and reported that the few family members in attendance had been “ice cold.” Over martinis one night at an old Clayton haunt, the Pump Room in Chicago, a director friend told Alex and me that he had had a one-night stand with Clayton just after graduating from Juilliard. Our friend promised he had more to tell but died before we could reconvene the conversation. Another reminiscence came from a colleague of Clayton’s in the mid-seventies, when he was in what was apparently his last theater job—as manager at the Martin Beck (now the Al Hirschfeld) on 45th Street. That was when New York City was in drop-dead mode and Broadway was all but abandoned, with more houses dark than not. Clayton had fallen into the habit of riding his bike from the East Side to the Beck in the dead of night to sit alone and play its old grand piano for hours with only the stage night-light for illumination. I seized on the theatrical slang for that lamp—“ghost light”—for the title of

my memoir, taking it as Clayton’s last, posthumous gift.

Once my book was published in 2000, I heard occasionally from others who knew Clayton. Their overall impression confirmed mine—he was magnetic, generous, and hilarious. Beyond that, there were more enigmas than explanations. One day I received a lengthy phone message from the actor Elliott Gould, who had roomed with Clayton for a few weeks on the road during the 1957 pre-Broadway tryout of an

unsuccessful musical in which he was a young chorus dancer and Clayton an assistant stage manager. He had not seen Clayton in the nearly half-century since then but had found him so captivating that he asked to meet so I could tell him more stories about him. He had had no idea Clayton was gay. Neither had Clayton’s roommate during a two-year apartment share in the late sixties. Recently I asked a friend of Clayton’s from his Chicago days, the veteran

Broadway dancer Harvey Evans, why Clayton remained closeted, at a time when gay performers like Evans were out to each other, at least within the confines of the theater. Evans speculated that it was because Clayton was a manager who had to deal with a company’s entire staff, the back office in New York, and the public, and didn’t want to take any risks, especially in a day when homosexuality invited police harassment and worse.

Ancient Gay History

ShareThis

Mining the archives at Lincoln Center’s performance-arts library for any additional evidence of Clayton, I found one incident that supported Evans’s theory in a letter deep in the files of the Broadway producer Leland Hayward. In 1963, Clayton had written to his immediate superior in New York about the abusive lead actor in a road company he was managing of the comedy

A Shot in the Dark. In Clayton’s telling, the star had accused him of “hand holding with a theatre manager and peregrinations in lobby of a theatre in San Francisco” and had addressed the show’s cast to deride him as an “eight-year-old little girl in boys pants from finishing school” who hated any “married man.” The actor threatened to “beat the shit” out of Clayton if he came backstage. Though Clayton toured for months with this show, neither it nor the offending actor ever turned up in the many behind-the-scenes tales he told me once our friendship began three years later.

The final glimpses I have of Clayton, near the end of his life, were courtesy of a reader who wrote me almost a decade after

Ghost Light was published. He and Clayton had worked together in the late seventies at M. Rohrs’, a small coffee-and-tea shop that survived until recently in the East Eighties. Clayton, now out of the theater, was at this point “cobbling together a living,” the reader wrote, working part time at Rohrs’ and at a bakery run by a friend. He was also “hustling bridge at the Cavendish Club.” Talking with Clayton was “a tutorial in graciousness, treating people well, and always presenting an enthusiastic front,” he recalled, adding that “an entourage began to appear” on the days Clayton worked. Clayton was still working at Rohrs’ when he took ill in 1983 or 1984. “He said it was lung cancer,” the letter went on, “but I was never sure if it was that or AIDS. I visited him a couple of times at his apartment, but it was clear that he was failing. The last time I saw him he was just hoping to hang on to get back to the beach on Fire Island with his friend (who I didn’t know) one more time.” Enclosed with the letter was a copy of a photo of the two of them outside the shop, with Clayton wearing the very un-Clayton accessory of a coffee vendor’s apron. “I have met a lot of exceptional people, but Clayton was truly special,” my correspondent concluded. “With the picture on our wall, hardly a day goes by when I don’t think of him.”

Who was that unseen “friend” Clayton was trying to get back to on Fire Island? Did he exist? As I embarked on this article, I decided to do one more round of sleuthing. When I wrote

Ghost Light, the Internet was not nearly as comprehensive a tool as it is today. Why not try to go way back once more? I searched for the girlfriend whom Clayton had partnered with those “Gayboys” back in Chicago; her last credit, in stock, was in 1967, and I could find nothing else. But I did locate another woman Clayton rhapsodized about

In his letters,

Diana Eden, who played one of the Pigeon sisters in his company of

The Odd Couple before migrating to Hollywood, where she built a career as a television costume designer. I reached her by phone at her current home in Las Vegas. Like me, Eden had lost touch with Clayton after those Chicago days, but when I asked her about their tearful parting when her

Odd Couple run ended, she described the 1 a.m. farewell scene at O’Hare much as Clayton had in a letter. She had adored him and, like others, had held on to old photos of him. “Clayton was very funny,” she recalled, “but that’s not the thing I most remember. There was an element of wistfulness and loneliness about him that I sensed strongly … I assumed from the beginning he was gay, but he never mentioned any love affair at all. He came to all the parties, but I never saw him with a date or touch anyone. But I felt immensely loved by him and taken care of.”

My final search was for a name I had been told when I was researching

Ghost Light—that of a man who might have been that “friend.” The name had been given to me by a woman who had known Clayton in his

Hair period. She was the only Clayton acquaintance I ever found who cited any specific lover. The man she named lived not on Fire Island but in Hawaii. I couldn’t find him in the late nineties. But this time he did turn up via Google: as the namesake of the

Clint Spencer Clinic at the Hawaii Center for AIDS at the University of Hawaii. I sent an e-mail to the Center asking for any biographical information that might be available.

Ancient Gay History

ShareThis

A nurse wrote me back empty-handed but pointed me toward others who might help. A doctor and HIV/AIDS researcher named Dominic Chow responded to my query. The clinic had been named after Spencer because he had been the first patient to participate in an AIDS study at the university, as well as “a strong HIV research and care advocate for the state of Hawaii” when HIV was first discovered in the eighties. “I knew Clint for the last two years of his life,” Chow wrote. “He was a warm and compassionate man” who fought hard “without compensation or need for recognition” to fight the epidemic and promote “compassion and respect to those infected.”

Chow sent a link to the

Honolulu Star-Bulletin obituaries of April 4, 2001. Spencer’s is just a few sentences long and makes no mention of his work on HIV/AIDS. The notice said he died at 53, named his domestic partner (of whom I could find no other trace), and described Spencer as “a retired stage director” born in New York. I tracked down his credits—he was indeed a stage manager for a few regional and Off Broadway productions in the seventies, though none of them intersected with Clayton’s theatrical orbit.

Thus the Clayton Coots story, like so many others of his time, trails off into fragments, ellipses, and mysterious dead ends. I’d like to believe that he did have a partner in his last years, and that he was taken care of as he had taken care of so many others in his peripatetic, too-brief life. But I can hardly say it for a fact. This being America, the next step for half-forgotten stories like Clayton’s will be to fade away altogether, just as the vanished, unmourned world where they unfolded already has. That’s progress, isn’t it?

I imagine that if Clayton were still here, he’d find the idea of same-sex marriage as far-fetched and funny as his favorite late-night movies. But, of course, I am speaking of the dashing public Clayton, who was “always Happy and with it.” There’s no way of knowing what the hidden Clayton would think. Like Harold Hill in

The Music Man, he might have found his someone and made a home. As the rest of us are swept up in the euphoria of weddings unimaginable only a decade ago, the least we can do is pause for a moment to remember him and all the others who were never given that choice.